“Within every man and woman, a secret is hidden, and as a photographer it is my task to reveal it if I can. The revelation, if it comes at all, will come in a small fraction of a second with an unconscious gesture, a gleam of the eye, a brief lifting of the mask that all humans wear to conceal their innermost selves from the world.”

Yousuf Karsh (1908-2002) was an Armenian-Canadian photographer famous for taking the definitive portraits of the men and women who shaped the twentieth century, and in particular his portrait of Winston Churchill in 1941, which is one of the most widely reproduced photographs in the history of photography.

Karsh belongs to that small elite group of artists whose work has not only affected our perception of people and ideas, but also helped to influence the course of history. The publication of his famous portrait of a 67-year old Winston Churchill, dubbed The Roaring Lion, on the cover of Life Magazine in 1942 is generally accepted as having played a large part in diverting the attention of the American public to the plight of Britain, and convincing them of Britain’s fighting spirit and determination to survive.

The photograph was made on December 30, 1941 when Karsh photographed the great wartime leaders in the House of Commons, in Ottawa after Churchill delivered his “Some chicken, some neck” speech on World War II to Canadian members of parliament. Churchill is particularly noted for his posture and facial expression, likened to the wartime feelings that prevailed in the UK – persistence in the face of an all-conquering enemy. The photo session was only to last 2 minutes. Karsh asked the Prime Minister to put down his cigar, as the smoke would interfere with the image. Churchill refused, so just before taking the photograph, Karsh quickly moved toward the Prime Minister and said “Forgive me, Sir” while snatching the cigar from his subject’s mouth. Karsh said, “By the time I got back to the camera, he looked so belligerent, he could have devoured me.” His scowl has been compared to “a fierce glare as if confronting the enemy.” Following the taking of the photograph, Churchill stated, “You can even make a roaring lion stand still to be photographed” thus giving the photograph its notable name. The resulting image – one of the 20th century’s most iconic portraits – effectively launched Karsh’s international career. A second photograph from the same shoot actually shows Churchill with a wry smile, as he comes around to the fact that somebody was so audacious to do such a thing.

Karsh had a special relationship with Britain, and following the international success of his Churchill portrait, in 1943 he boarded a Norwegian freighter containing a cargo of explosives which was bound from Canada to Britain, and stayed in London to photograph wartime leaders and intellectuals. Many of these photographs were published in the Illustrated London News and played their own part in raising the nation’s morale during WWII. He returned to Britain many times throughout his 60-year career and on one of his visits in 1976 he photographed the Rt Honourable Margaret Thatcher.

Karsh’s ability to produce the ‘definitive’ portrait of so many of the great men and women who shaped the 20th century, not only Churchill, but Kennedy, Khrushchev, Castro, Hemingway and others, was not achieved lightly. In addition to the long sittings he often required, he researched his sitters thoroughly before meeting them, and his careful studio lighting, which he first learned with the Ottawa Little Theatre in the 1930s, is legendary. Courage, too, was required, for who else would have dared to pull the cigar from Churchill’s mouth or persuaded Khrushchev to dress up in a large fur coat?

Over the decades that followed, he made many notable portraits, including those of Georgia O’Keefe, Dwight Eisenhower, Albert Einstein, Martin Luther King, Mother Teresa, Nelson Mandela, Princess Elizabeth, Marilyn Monroe and Muhammad Ali. Karsh retired in 1992, and later relocated to Boston where he died in 2002 aged 93. Today, his works are held in the permanent collections of the National Gallery of Canada, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the National Portrait Gallery in London, among others.

“Within every man and woman, a secret is hidden, and as a photographer it is my task to reveal it if I can” Karsh once explained. “The revelation, if it comes at all, will come in a small fraction of a second with an unconscious gesture, a gleam of the eye, a brief lifting of the mask that all humans wear to conceal their innermost selves from the world.”

Karsh was an Armenian genocide survivor, who migrated to Canada as a refugee in 1923. By the 1930s he established himself as a significant photographer in Ottawa, where he lived most of his adult life, though he travelled extensively after his portrait of Churchill in 1941, which was a breakthrough point in a 60-year career. His extraordinary and unique archive of work presents the viewer with an intimate and compassionate view of humanity. During his career, he held 15,312 sittings and produced over 370,000 negatives, and left an indelible artistic and historical record of the people who shaped the era.

Signed prints of Karsh’s portrait of Churchill in 1941 were produced as silver gelatin prints from his studio. They were signed as “© Y Karsh Ottawa” in white marker in the lower left or lower right corner. This later changed to Karsh signing in ink on one of the lower corners of the white border surrounding the photograph. Early print sizes ranged from 8.5 x 11 inches (220 x 280mm) or 11 x 14 inches (280 x 360mm) then progressed to 16 x 20 inches (410 x 510mm) and 20 x 14 inches (510 x 610mm) respectively in later years. The original negatives of Karsh’s work were donated by his estate to the Library and Archives Canada in 1992, and since then, copies taken from the original negatives have not been allowed.

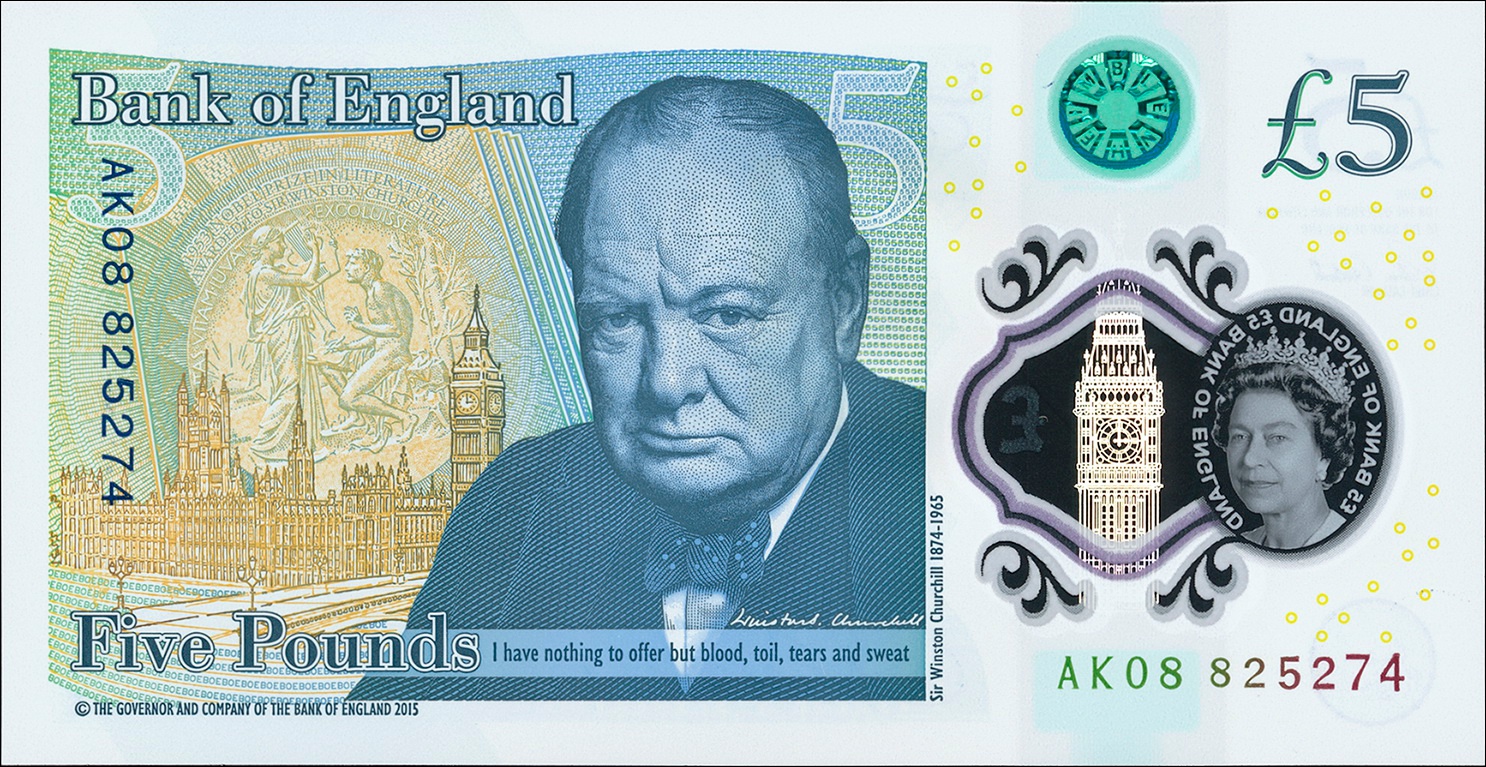

Since 2013, Karsh’s 1941 portrait of Churchill has appeared on the £5 note issued by the Bank of England.