In the decades after its invention in 1830 photography was used mainly for producing scientific and representational images, and was the preserve of a wealthy elite. Pictorialism was a movement that thrived between 1885 and 1915, and began in response to claims that a photograph was nothing more than a simple record of reality. It transformed into an international movement of exhibiting photography societies to advance the status of photography as a true art form, and have the same status as paintings and sculpture.

The Railroad Yard, Winter 1903 by Alfred Stieglitz

Pictorialist photographers approached the camera as a tool that, like the paintbrush or chisel, could be used to make an artistic statement. They strived to elevate photography as a medium and have it recognised by art museums and galleries. First and foremost, their photographs placed beauty of subject matter, tonality and composition above creating an accurate visual record.

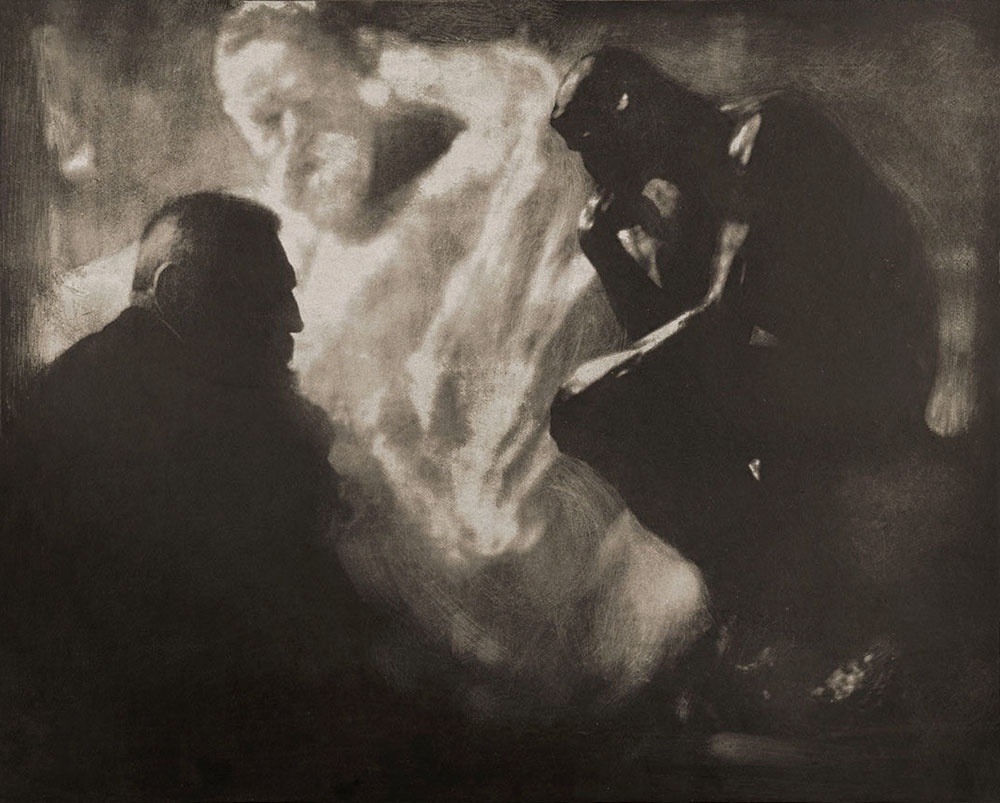

Rodin Le Penseur 1902 by Edward Steichen

Pictorialism had its roots in England until 1890 when the centre shifted to New York, where it centred around Alfred Stieglitz (1864 to 1946), the most influential amateur photographer of his era and a vital force in the development of Modern art in America. By 1900, pictorialism had reached countries all around the world where groups of photographers had established their own exhibiting societies. The two most active societies were the Linked Ring Brotherhood (founded in 1892) in England and the Photo Secession (founded in 1902) in the USA.

WHAT ARE THE CHARACTERISTICS OF PICTORIALIST PHOTOGRAPHS?

Pictorialist photographers were horrified by the growing use of photography in science and industry and the mass of weekend snap shooters that emerged after the advent of the Kodak camera in 1888, which was marketed under the slogan ‘No knowledge of photography is necessary; you press the button, we do the rest.’ They wanted photography to be a fine art, not a commercial activity that anyone could do. To this end they deliberately used complex and lengthy printing processes like photogravure, involving substances such as carbon, gum, platinum, and bromoil to enrich their prints and toning to add colour - most of which resulted in prints that looked attractively smudged and velvety, like charcoal drawings or lithographs. They made the production of a photographic print by hand much closer to the creation of a painting.

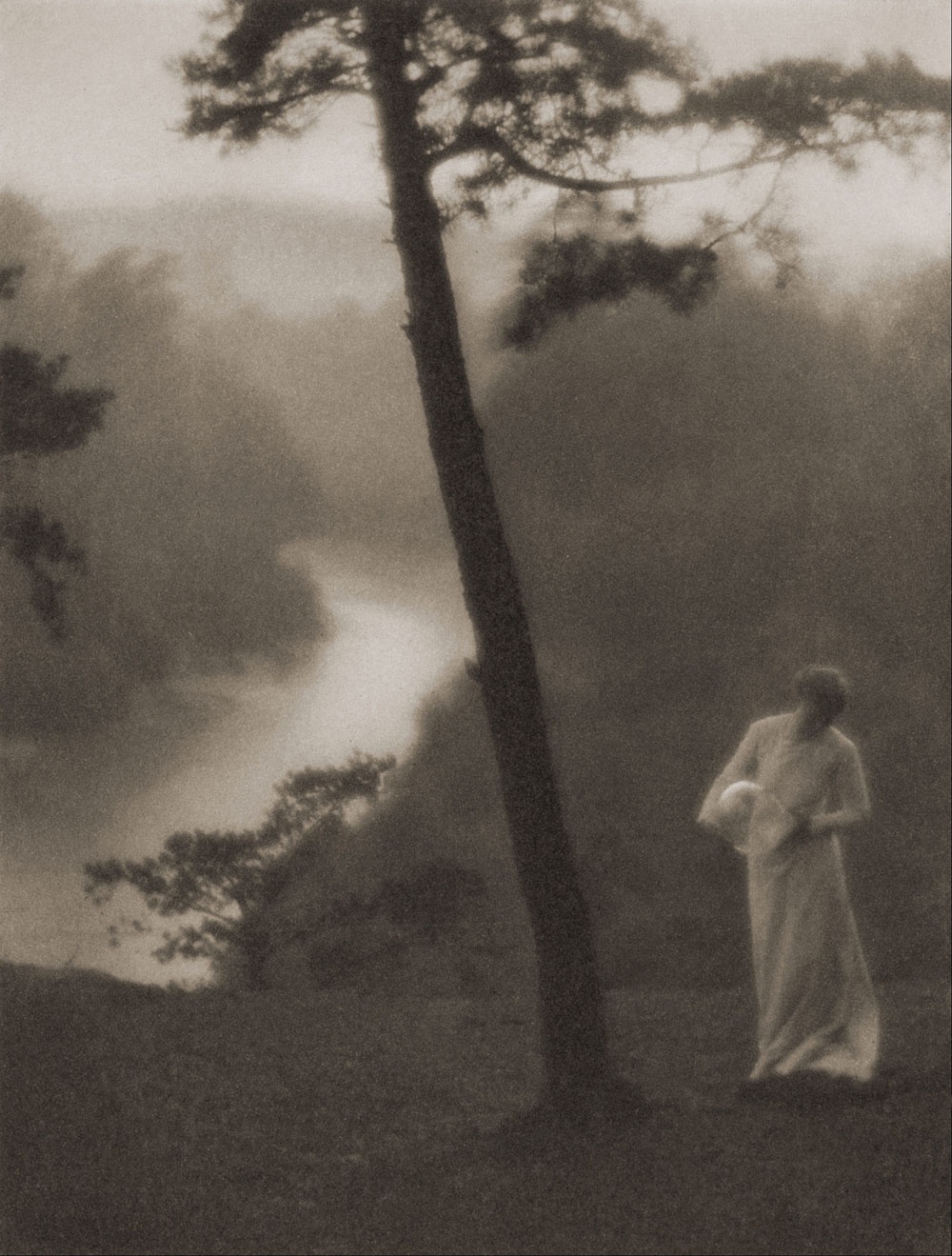

Morning 1908 by Clarence H White

Typically, a pictorial photograph had a soft focus, was printed in one or more colours other than pure black and white (ranging from warm brown to deep blue) and may have had visible brushstrokes or other manipulation of the surface. For the Pictorialist, a photograph, just like a painting, drawing or engraving was a way of projecting an emotional intent into the viewers realm of imagination. Artists sought to bring to photography the impressionist qualities of 19th century painting through an emphasis on the atmospheric elements in the picture by the use of vague shapes, soft edges and subdued tones. Artists often worked at night, or in mist or snowy weather using soft-focus lenses with gauze or scrim (an open weave fabric) to blur images. Pictorialist prints were darker than we are used to seeing today, and noted for their subdued highlights.

WHO WERE THE MOST IMPORTANT PICTORIALIST PHOTOGRAPHERS?

England had the longest tradition of pictorial photography and until 1890 was the main country where it was practised. In May 1892 Henry Peach Robinson (1830-1901), George Davison (1854-1930) and Henry Van Der Weyde (1838-1924) established a group of pictorial photographers into an exhibiting society formerly known as the Linked Ring Brotherhood.

In 1902 Alfred Stieglitz formed the American Pictorialist photographers into a group called the Photo Secession movement. The core group comprised Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946), Alvin Langdon Coburn (1882-1966), Frederick Holland Day (1864-1933), Frank Eugene (1865-1936), Gertrude Käsebier (1852-1934), Edward Steichen (1879-1973) and Clarence White (1871-1925).

The Linked Ring was one of a string of similar groups in Paris, Berlin, Brussels and Hamburg. True to its Masonic roots, membership was by invitation only, to “those who are interested in the development of the highest form of Art of which Photography is capable.” All the members were men until Gertrude Käsebier was invited in 1900. By holding an annual exhibition from 1893 and publishing a journal from 1896 to 1909, the Linked Ring had a long-lasting influence on photography.

The Old Order And The New, 1885 by Peter Henry Emerson

Peter Henry Emerson (1856-1936) was an advocate of selective focus in which depth of field was limited to the main subject. He believed that extensive depth of field in which everything is in sharp detail led to spatially dreary results.

Village Under The South Downs, 1901 by George Davison

George Davison (1854-1930) went further in Village Under The South Downs, 1901 when nothing is in sharp focus in this romantic and impressionistic vision of rural England, and the blurry quality is enhanced by printing on rough textured paper.

Spring Showers, 1900 by Alfred Stieglitz

Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) explored the New York streets at night often photographing in wet, misty conditions such as in Spring Showers, 1900. The composition of this image shows the influence of Japanese art, then much in vogue, and was printed on thick semi-translucent Japanese vellum.

WHAT WERE THE MOST IMPORTANT PICTORIALIST PHOTOGRAHS?

Alfred Stieglitz, Alvin Langdon Coburn and Edward Steichen were some of the most active photographers of the Pictorialist era. Stieglitz was the driving force and his significance lies as much in his work as an art dealer, exhibition organiser, gallery owner, publisher and writer. A culminating moment for photography occurred in 1910 when the Albright Gallery in Buffalo, New York acquired 15 photographs from Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery. This was the first time photography was officially recognised as an art form worthy of a museum collection, and it signalled a definite shift in many people’s thinking.

Reflections, New York 1898 by Alfred Stieglitz

Stieglitz used natural elements such as rain to bring his compositions together. In this study, light reflecting on the wet pavement makes a glimmering backdrop to the silhouetted trees. His stated aim was to create a vision of New York that would be as beautiful to its citizens as Paris was to Parisians.

WHEN WAS THE PERIOD OF PICTORIALISM IN PHOTOGRAPHY?

Pictorialism was one of the most interesting periods in the history of photography, and was the culmination of an argument that had been raging in the second half of the 19th century about whether photographs could be valued as art - in the same way as paintings and sculpture. The differences between straight and manipulated photographs were debated with an almost religious fervour – the future of photography itself appeared to be at stake. Real or not real, painterly or not, art or merely science, such topics provoked heated debate.

The movement had its heyday between 1880 and 1915 when exhibiting societies and photography galleries were established all over the world, culminating in the acquisition of photographs by several major art museums, a landmark moment for the medium.

But World War I changed everything and pictorialism gradually declined in popularity after 1920. As the harsh realities of war affected people around the world, the public’s taste for the art of the past began to change. Developed countries focused more and more on industry and growth, and art reflected this change by featuring hard-edged images of new buildings, aeroplanes and industrial landscapes. During this period the new style of Modernism came into vogue, and the public’s interest shifted to more sharply focused images.

The Steerage, 1907 by Alfred Stieglitz

Towards the end of his life Stieglitz wrote “If all my photographs were lost and I were to be remembered only for The Steerage 1907, I would be satisfied.” Taken on a voyage to Europe in 1907 on the SS Kaiser Wilhelm II, one of the most luxurious liners of the time, Stieglitz and his family were travelling first class. Stieglitz recounted that when he explored the ship, he saw people from the steerage class enjoying the fresh air. He rushed back to his cabin, loaded his camera with the one unexposed glass negative he had, returned to the scene and made the exposure.

The Steerage, 1907 was a turning point in Stieglitz’s thinking about the medium of photography. Instead of aiming to recreate fine art ideals of the past, he switched to Modernist values, looking forward to the machine age, construction and science (which would come at the end of World War I). Captured with a Modernist framework of walkways and chimney, the visual contrast between the upper and lower decks literally divides the social classes. The photograph is both of its time and well ahead, anticipating the spatially articulated documentary photographs of Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908-2004) and Sebastião Salgado (b.1944).

Is this of interest? Please add your comments below…